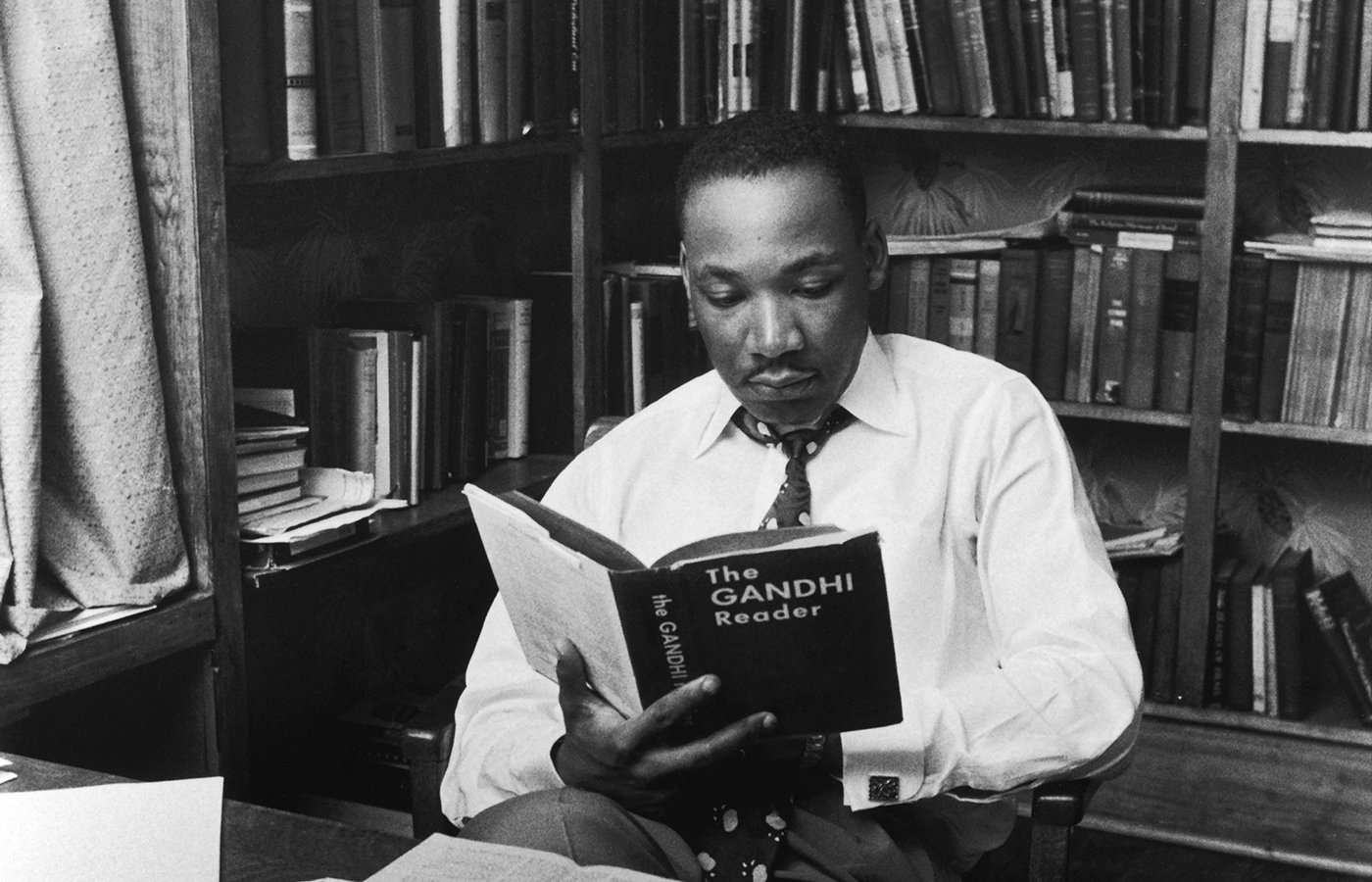

"It is no longer a choice between violence and nonviolence in this world; it's nonviolence or nonexistence."

— Martin Luther King Jr., “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution,” 1968

Welcome to our Explore Page. Whether you’re new to nonviolence study or are a long-term practitioner looking for strategies and support, you’re in the right place.

This page is divided into two key sections: Foundations of Nonviolence and Nonviolence in Action. Each has materials for further study and ideas for action.

NOTE: We do not say “new to nonviolence” because each one of us has nonviolence inside of us and we encounter its power every single day, whether or not we recognize it! Through deeper study and attention to it, you’ll begin to develop your capacity for drawing upon it and using it with more awareness and with greater power at your disposal.

Foundations of Nonviolence

Nonviolence is also known as “love in action.” As a constructive power, it’s unleashed when potentially destructive drives like fear or anger are converted into creative equivalents like love and compassion. Nonviolence, when harnessed systematically and in an experimental, scientific spirit, can be used as a force for realizing greater security, justice, and social unity. In the words of Mahatma Gandhi, “nonviolence is the greatest power at the disposal of humankind.”

A working definition of nonviolence is an important first step. Putting it into practice is another.

The Power of Transformation

In 1992, terrible riots broke out in Gandhi’s home state of Gujarat when an armed “Hindu” mob descended on a rural village with the aim of killing Muslims. Almost all the village men had been out in the fields working. The women reacted quickly, however, and gave their Muslim neighbors refuge in their homes. As most of the villagers lived in one-room cottages, the women safeguarded their Muslim neighbors in near-plain sight, underneath their household altars.

The mob stormed up to one home screaming, “Are you hiding a Muslim in there?!” “Yes,” the woman inside calmly replied. Somewhat nonplussed, the men barked, “We are coming in to get them!” Then the woman with equal calm said, “First kill me, then only you may enter.” As though by some prearrangement, each of the village’s women responded the same way to the mob. Virtually every Muslim in that village—and some others who didn’t live there—was saved.

How can we explain the women’s power in overcoming the threat of armed men at their doors? In his book The Three Faces of Power, economist Kenneth Boulding coined terms for three kinds of power. “Threat power” is a coercive force that can be summarized as You do something I want, or I will do something you don’t want, and it’s this type of power that the crazed mob in the Indian village wielded. Threat power can be effective in achieving a result for the one wielding it, but it damages the relationship and creates distance between the two parties. In the long run, it always makes things worse.

A second type of power, exchange power, is neutral: If you give me something I want, I will give you something you want. The parties make a mutually agreeable trade in which no one is coerced, and while the two are not driven apart, they’re not brought much closer together. The third kind of power Boulding refers to is “integrative power,” and it’s what the village women in the story above tapped into. Integrative power is more subtle. Boulding formulates it this way: “I will be authentic, and it will bring us closer together.”

Transforming conflict into strengthened relationships through persuasion rather than coercion is nonviolence.

Love & Wisdom

There is a source of love and wisdom in every person, in many ways and in all kinds of relationships. With the relationship of conflict at its core, integrative power, or nonviolence, evokes a deep response in an onlooker or an opponent, whether the response arises to the surface or not. In the last 20 years or so, science has found more evidence for the existence of nonviolent power within us as well as its predictable effect on others.

Biologist Mary Clark identified three basic human needs beyond the physical needs of food, clothing, and shelter: bonding, autonomy and meaning. That the village Hindu women above were willing to die alongside their Muslim neighbors unleashed a persuasive effect on the armed men. This true story illustrates the deep power of appealing to the human need for bonding and integration with others. It brings us to another good working definition of nonviolence, to add to the one we started with at the top of this page:

Nonviolence arises from the conversion of a negative drive, such as anger or fear, into constructive action. It can be cultivated systematically, and in this sense we could say that nonviolence is the science of appealing to the human need for integration.

Metta Center founder and president Michael Nagler gives this illustration in his American Book Award-winning The Search for a Nonviolent Future:

I am thinking of the anger Gandhi experienced that fateful night of May 31, 1893, when he was thrown off the train at Pietermaritzburg a week after his arrival in South Africa. This was no minor irritation; according to his own testimony, Gandhi was furious. That, along with the fact that Gandhi is more than usually articulate about his inner experiences, is what makes this event (among millions of similar insults human beings endure at one another’s hands) such an important window into the dynamics of nonviolent conversion. The first clue as to how he finally succeeded, after a night of bitter reflection, to see the creative way out is that he didn’t take the insult personally; he saw in it the whole tragedy of man’s inhumanity to man, the whole outrage of racism. Not “they can’t do this to me,” but “how can we do this to one another?” The second clue is the state of his faith in human nature. Already at that period he believed that people could not stay blind to the truth forever. He did not yet know how to wake them up; he just knew they could not want to stay forever asleep. That is how he was able to find the third way between running home to India and suing the railroad company. Imagine the old-fashioned locomotive carrying this “coolie barrister” from Durban up the mountains to Pretoria, standing at the station in Pietermaritzburg with a good head of steam. You could shovel in more coal and just bottle up all that power and even pretend it wasn’t there, until finally it exploded, or you could just open the valves and scald everyone on the platform—but surely you would want to use it to drive the train. This is what Gandhiji was going through with all the emotional power built up in him by the accumulated insults he had met since his arrival at the Durban pier. He chose neither to “pocket the insult,” as he said, nor to lash out at the immediate source of the pain. He launched what was to become the greatest experiment in social change in the modern world.

Following his experience at Pietermaritzburg, Gandhi went on to develop active nonviolence as a form of resistance that he came to call Satyagraha, literally “clinging to truth” (it’s sometimes translated as “truth force” or “soul force”). An excellent example of Satyagraha can be found in Richard Attenborough’s 1982 film Gandhi, the scene in which Gandhi gives a speech to Hindu and Muslim Indians in the Empire Theatre in South Africa, after the British Raj passed repressive laws requiring, among other things, fingerprinting of all Indians. The event portrayed in the film is historically accurate, but the speech in the film, though true in spirit to Gandhi, should not be taken word for word. (Read an excerpt of the film speech below the video player.)

Excerpted film speech:

In this cause I, too, am prepared to die, but, my friends, there is no cause for which I am prepared to kill. Whatever they do to us we will attack no one, kill no one, but we will not give our fingerprints. Not one of them. They will imprison us. They will fine us. They will seize our possessions. But they cannot take away our self respect if we do not give it to them. I am asking you to fight. To fight against their anger, not to provoke it. We will not strike a blow, but we will receive them. And through our pain we will make them see their injustice. And it will hurt, as all fighting hurts. But we cannot lose. We cannot. They may torture my body, break my bones, even kill me. Then, they will have my dead body, not my obedience.

Gandhi’s Satyagraha was grounded in the ancient principle of Ahimsa, translated into English as nonviolence but in its original Sanskrit implies “the power released when all desire to harm is overcome.” In the nonviolent approach to conflict, we aim to resist wrongs without resisting people—no wishing them harm or doing anything to compromise their long-term well-being and fulfillment.

Person Power, Constructive Program, Satyagraha

Person Power

Nonviolence begins inside of each one of us, and is the greatest power of our human nature. Individuals can affect positive change with or without large groups. Everyone has a role to play.

Constructive Program

By nature, nonviolence has more to do with building up than tearing down. Even when it obstructs some injustice, the goal is to allow some justice to prevail. Often by building what we want, what we don’t want will either stop or be much easier to stop because we’re offering an alternative. This is the most overlooked and possibly strongest power in nonviolence.

Satyagraha/Obstructive Program

It breaks down into two parts: Satya-Truth, graha-Hold Fast to. This is Truth-force or Love-force. We resist injustice without reproducing it. We obstruct hatred and violence with a firmness rooted in love.

Where do you see yourself in the Roadmap?

At the Metta Center, we’ve developed a Roadmap as a way to visualize the movement for nonviolence. Notice that it has three concentric circles, beginning in Person Power, extending through Constructive Program, with Satyagraha on the outermost ring. It is a model of empowerment: by strengthening our person power, our constructive programs are that much more effective; and when our constructive programs are more effective, our obstructive program is more powerful. Equally important is the top center wedge, New Story Creation. Nonviolence is within a different paradigm altogether and requires a more accurate understanding of human nature than is currently embraced by our political and mass media culture.

A New Story of Human Nature

At the Metta Center we emphasize that nonviolence operates from a different framework or story than our commercial mass media culture. We are not just separate bodies fighting for scarce resources on a finite planet. We are body, mind, and spirit. Our interconnection is fundamental to who we are and that is why nonviolence is so powerful.

This ‘new story, ’ including the power of nonviolence, is backed by all fields of science, especially neuroscience and quantum physics. History and other social sciences have also contributed a great deal to unlocking what nonviolence can do when practiced systematically and with dedication. (This rich history is archived at the Global Nonviolent Action Database at Swarthmore College.)

This story or framework is also at the root of the compelling power of nonviolent institutions such as Unarmed Civilian Protection, Restorative Justice, and economic models based on cooperation and mutual aid instead of competition and mere material accumulation. This framework models a far healthier relationship to the natural environment, with each other and all beings, and especially within ourselves, i.e. what we call “the Third Harmony.”

Five Things Everyone Can Do for Nonviolence (from the Inner Circle of the Roadmap):

Unplug from the commercial mass media and its low image of the human being. There are more accurate ways of finding information about current events that do not degrade human nature. Find them!

Learn everything you can about nonviolence. Starting here with the Metta Center will provide a strong foundation and support.

Take up a spiritual practice like meditation in order to build inner strength, a fresh perspective, and a way to form and strengthen a mechanism to transform fear and anger.

Practice humanization by being more personal with everyone. See our common humanity within our diversity. Honor both our unity and our diversity.

Take action and tell the new story. Find where your gifts meet the needs of the movement for peace and nonviolence and get involved. Explain and emphasize our interconnectedness with your words and actions.

News Resources:

Learn directly from involved individuals, organizations and groups what they are doing. These stories do not often make the mainstream news. Ex. Have you heard of Combatants for Peace?

Nonviolence in Action

Nonviolence is an infinitely creative power that has real-world applications for movements for democracy, social justice, and freedom. It can overcome intense oppression and repression and change relationships from enmity to ubuntu. There are no limits to its power, and it benefits not only the situation that it is used in, it can heal and transform the person wielding it.

When we use nonviolence, it means we do conflict better and we improve relationships along the way, which is one of the goals of nonviolent struggle. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “the aftermath of nonviolence is the Beloved Community.”

The distinction, “work” vs. work, is necessary to stress that the beneficial results of nonviolent action often lie in the future. “Work” means the immediate and obvious effects, while work without quotes designates the resulting underlying and fundamental shifts brought about by nonviolence. In other words, it means not “got what we wanted,” but rather, “does good work.” All action has consequences on various levels. A nonviolent actor always takes into account the intended long-term objectives and consequences and not just the more expedient or visible results. Because nonviolence can take time to address root causes of violence or injustice, people seeking immediate objectives often reject it on the grounds that nonviolence doesn’t “work.” Often they embrace violence because it satisfies an immediate need. Unfortunately, ignoring the fact that violence often fails to “work” and its long-term adverse consequences lead to lurching from crisis to crisis instead of steady improvement.

One can characterize this concept as follows:

Violence sometimes “works” but never works, while nonviolence sometimes “works“ and always works.

Gandhi’s Salt Satyagraha of 1930 is a classic example of this concept. At the cost of much suffering, the campaign produced virtually no change in the hated salt laws but historians have identified it as the turning point that lead to the independence of India 17 years later.

“Work” vs. Work

Nonviolent Civil Resistance Works.

This video from Professor Erica Chenoweth, co-author of Why Civil Resistance Works, puts the practice of nonviolence as civil resistance into quantifiable terms, such as Nonviolence, when used, is twice as likely to succeed than violent struggle. Factors include: mass mobilization, innovative tactics, loyalty shifts, and resilience building.

But would it have worked against the Nazis?

The answer might surprise you. When it was tried against Nazism, it both “worked” and worked.

It’s important to remember that nonviolence isn’t the same as passivity—it’s an active force for resistance. In fact, there were numerous examples of nonviolent resistance to the Nazis, even if they weren’t widely remembered or supported at the time. In places like Denmark, Bulgaria, and even parts of France and Germany, people resisted deportations, protected Jewish neighbors, and organized strikes and protests. These actions saved lives and challenged the regime in ways that didn’t rely on armed struggle.

What’s more, the Nazi regime thrived on dehumanization and domination. Nonviolent resistance—when it’s strategic and rooted in truth—undermines that logic by asserting shared humanity and moral courage. Of course, nonviolence alone might not have stopped the Holocaust once it was in full force. But a global, earlier, and better-organized nonviolent response to fascism, racism, and antisemitism could have made genocide much harder to carry out. So the question might not be ‘Could it have worked?’ but ‘How do we build a world where such a regime never gets that far?’ In other words, how to build a world where nonviolence is the norm?

Two Hands of Nonviolence

“With one hand we say to the oppressor, ‘Stop what you are doing.’ With the other hand, we say, ‘I won’t let go of you.’”

—Barbara Deming

The Two Hands of Nonviolence, a concept articulated by late feminist writer and journalist Barbara Deming, offers a powerful image of how nonviolence engages conflict. With one hand, we say “Stop”—we firmly refuse to cooperate with injustice or harm. This hand sets boundaries and stands strong in truth. With the other hand, we say “I won’t let go of you”—we hold onto the humanity of the person we oppose, refusing to turn them into an enemy. Together, these hands express the heart of nonviolence: resistance without hatred, and love without submission. It’s a practice of courage, dignity, and deep belief in transformation.

Suggested Reading/Study/Resources:

All of the resources from the Foundations of Nonviolence, PLUS:

Nonviolence Principles and Strategies

Nagler’s Peace and Conflict Studies Lectures

Actions:

All of the actions from the Foundations of Nonviolence, PLUS:

Network and train with other nonviolence organizations and trainers, such as Nonviolence International, Nonviolent Peaceforce (and other unarmed civilian protection organizations) and new organizations such as the Nonviolent Action Lab, the Horizons Project (US-based) and the Strategic Nonviolence Academy.

Quick Links: