Lesson 5: Needs-based Economy

Objectives:

Explore and familiarize yourself with case studies of organizations and individuals working on a needs based economy

Think strategically about constructive programme in the context of this sector

Think through obstructive efforts to economic injustice

Introduction

Constructive program (CP) was the backbone of the successful struggle to liberate India from foreign rule, but it cannot be said that modern India has built its economy on those principles. So far, that has been the road not taken for the national economic policy. The grip of the old story makes faith in the principles of CP very difficult. But they are being carried out on a small scale by innumerable social experiments in India and around the planet. And sometimes the scale is not so small.

Michael Nagler describes an example in The Third Harmony:

“Down the county from my community, in San Rafael, there’s a great bakery and café called Arizmendi’s. It’s named for Father José Maria Arizmendiarrieta, who founded the Mondragón cooperatives in the Basque region of northern Spain in 1956. The San Rafael Arizmendi café/bakery is not affiliated with Mondragón except in spirit, which means that its worker owned and reflects many of the ten Basic Co-operative Principles of Mondragón: Open Admission, Democratic Organization, Sovereignty of Labor, Instrumental and Subordinate Nature of Capital, Participatory Management, Payment Solidarity, Intercooperation, Social Transformation, Universality, and Education.

The success of the Mondragón cooperatives at the old-fashioned bottom line is not unusual; it’s also seen in many economic experiments, some of which are a good bit more radical: transition towns, local cooperatives, worker-owned firms, farmers markets, gift economies, local currencies. As for alternative financial institutions, they range from credit unions that are replacing banks or anything too big to fail, to the hugely successful microlending model invented by Mohammed Yunus, who started the Grameen Bank system in Bangladesh in 1983.”

In this section we will look more deeply into examples like these given in the Roadmap and The Third Harmony.

Gandhian Economics

Begin by listening to this podcast from Nonviolence Radio with Professor Michael Allen, Professor Michael Nagler, and Stephanie Van Hook (Metta Center’s Executive Director and host of Nonviolence Radio).

Gandhian economics is largely characterised by rejection of the concept of the human being as a rational actor always seeking to maximize material self-interest that underlies classical economic thinking. Where Western economic systems are based on what he called the “multiplication of wants,” Gandhi felt that this was both unsustainable and devastating to the human spirit. His model, by contrast, aimed at the fulfillment of needs – including the need for meaning and community. The resulting model reflected elements of the New Story vision of human nature and human needs (not unlike some elements of psychologist Abraham Maslow’s ‘hierarchy of needs.’ Needless to say, it adheres to the principles and objectives of nonviolence; for example, it rejects class war and renders it unnecessary by introducing trusteeship to replace ownership: owners and managers would learn to regard their possessions as given to them in trust by the community and for the benefit of the entire community, including their own.

Gandhi promoted national self-sufficiency (swaraj), incorporating civil resistance as a means to that goal. He targeted European-made clothing and other products as not only a symbol of British colonialism but also the cause of mass unemployment and poverty, and encouraged people to make homespun 'khadi' clothing. In his earliest campaigns in India he led farmers of Champaran and Kheda in civil disobedience and tax resistance campaigns against the landlords supported by the British government, as well the mill workers of Ahmedabad in an effort to defend their economic rights and end oppressive taxation and other policies that forced the farmers and workers into poverty. A major part of this rebellion was getting a commitment from the farmers to end caste discrimination and oppressive social practices against women while launching a co-operative effort to promote self-sufficiency by producing their own clothes and food. Gandhi's concept of egalitarianism was centred on the preservation of human dignity rather than material development. As he wrote, “I do want growth, I do want self-determination, I do want freedom, but I want all these for the soul. . . It is the evolution of the soul to which the intellect and all our faculties have to be devoted.”

The first principle of Gandhi’s economic thought is ‘plain living’ which helps in cutting down your wants and making you self-reliant (thus independent of British rule). This would obviate a great deal of violence, as the most exploitative economic practices historically have not been focused on basics as much as “wants:” sugar, coffee, and of course drugs.

The second principle is small-scale and locally oriented production, using local resources and meeting local needs (svadeshi), so that employment opportunities are made available everywhere, promoting the ideal of the welfare of all (sarvodaya), in contrast with the welfare (or surplus) of a few. The third principle, trusteeship, is that while an individual or group of individuals is free to make a decent living through economic enterprise, their surplus wealth above what is necessary to meet basic needs should be held as a trust for the welfare of all, particularly of the poorest and most deprived. Trusteeship would eventually replace ownership, and a transition to trusteeship would obviate the need for forcible revolution to achieve equity.

Gandhi thus advocated, to sum up, trusteeship, decentralization, labour-intensive technology and priority to the weaker sections of society. He held that industrialization on a mass-scale, centralization, and capital accumulation will lead to passive or active exploitation of the people, as they would inevitably involve competition and artificial marketing. However, he did not oppose manufacturing for basic needs, even if it involved modern machines and tools.

Gandhi’s focus on local self-sufficiency meant far less exploitation of nature than is seen in Western economics. Michael Nagler once asked E. F. Schumacher, a pioneer of the new economy, “Wouldn’t you say that the whole appropriate technology movement you write about really grows out of Gandhi’s spinning wheel?” “Absolutely,” he answered proudly. Schumacher pointed out that we’re consuming the capital of nature instead of her interest—that is, using up non-renewable resources like coal and oil instead of renewable ones like wind and sunlight. We can live off the “interest” of nature indefinitely, but as any economist will point out, once you spend the capital, it is gone. But there’s more. When we push on, into the realm of the third harmony, the reservoir of our inner resources, we discover something remarkable indeed: resources like love, dignity, and courage are beyond renewables: they grow with use!

Modern day examples

Let’s start with sharing some more details about the Mondragón cooperatives. Cooperatives had been common in Basque country (in the North of Spain) but had all but died out in the civil war, pushing the region into poverty. In the Mondragón corporations, all workers are stockholders—if you don’t have the capital to buy shares when you’re first hired, a portion of your salary is company stock. Importantly, anyone can attend Mondragón University—free of charge, as education ought to be—and go on to become a manager. Your salary will be limited to three times that of a line worker—not three hundred times higher, as it commonly is in American corporations, and if you perform poorly as a manager, you are simply given some other role. Most importantly, the wide variety of capital and household goods manufactured in the network—a decision that involves all workers—does not include military hardware. Not everything is rosy even in this most advanced business culture, but both the human and economic bottom lines are highly impressive success stories that I’ll say a bit more about later on. The Mondragón cooperatives have become one of Spain’s most successful enterprises, with nearly €12 billion in annual income earned by 74,117 employees in 260 businesses and cooperatives operating in forty-one countries. None of the earnings, remember, comes from the manufacture of or investment in weapons.

The success of the Mondragón cooperatives is not unusual; it’s also seen in many economic experiments, some of which are a good bit more radical: transition towns, local cooperatives, worker-owned firms, farmers markets, gift economies, local currencies. As for alternative financial institutions, they range from credit unions that are replacing banks or anything “too big to fail”, to the hugely successful microlending model invented by Mohammed Yunus, who began life as a conventional economist but realized that a system that kept people in dire poverty rather than helping them get out of it was fundamentally flawed. So he started the Grameen Bank system in Bangladesh in 1983. Today Grameen has 2,564 branches, with 19,800 staff serving 8.29 million borrowers in 81,367 villages—and Yunus has a Nobel Prize. On any working day Grameen collects an average of $1.5 million in weekly installments. Of the borrowers, 97 percent are women, and over 97 percent of the loans are paid back, a recovery rate far higher than that of any traditional banking system. Often loans that are ludicrously small by our standards are enough for a village woman to buy, say, a bit of bamboo to make stools or some seeds for her vegetable business. They are too small to fail! And they do a tremendous lot of good. Grameen methods are applied in projects in fifty-eight countries, including the United States, Canada, France, the Netherlands, and Norway.

The Third Harmony was published by Berrett-Koehler, one of several thousand B Corps and benefit corporations that have set out with a new triple bottom line of people, planet, and profit—a step beyond the socially responsible funds that simply avoid military and economically damaging investments. Today, there is a growing community of more than 1,400 certified B Corps in forty-two countries and over 120 industries working to redefine success in business; they’re about using business as a force for good. Michael writes that he was included and heard from at every stage of the process, from choosing the cover to the marketing needed to get such a “specialty” item to its readers. Nonviolence, as you can imagine (and as I know from experience) is not a hot item out there in the market; yet because of the culture that Berrett-Koehler founder Steve Piersanti had been able to instill in the firm, he told his acquisitions editor, “We’re going to do this book even if we lose money on it.” (Which they did not.) Berrett-Koehler was then a B corporation; today they are a benefit corporation, which gives legal status to businesses who want to expand corporate purpose beyond maximizing share value to explicitly include social and environmental goals. That language is from California’s statutes, and similar language is found now in the relevant statutes of thirty states. Two thousand for-profit corporations now have this status. In non-legal terms, such corporations are also known as “social enterprises”.

Probably the closest example of Gandhian economics you can find today are also experiments in beloved community: the 'transition towns' (TT): grassroot community projects that aim to increase self-sufficiency to reduce the potential effects of peak oil, climate destruction, and economic instability. It is about communities stepping up to address the big challenges they face by starting local. By coming together, they are able to crowd-source solutions. They seek to nurture a caring culture, one focused on supporting each other, both as groups or as wider communities. Although the main inspiration for these initiatives come from permaculture, there are overlaps with the Gandhian economic values, such as localism. (For a list of their principles visit their website). Food, for example, is a main focus of a TT, which creates community gardens and replaces ornamental tree planting with fruit or nut trees.

The 2006 founding of Transition Town Totnes, in the United Kingdom, became an inspiration for other groups. The Transition Network charity was founded in early 2007, to support these projects. Transition initiatives have been started in locations around the world, with many in the United Kingdom and others in Europe, North America and Australia. While the aims remain the same, Transition initiatives' solutions can vary with the characteristics of the local area. In practice, the Transition Network writes, transition towns are reclaiming the economy, sparking entrepreneurship, reimagining work, reskilling themselves and weaving webs of connection and support.

After the 2008 global financial crisis, the Transition Network added financial instability as further threat to local communities. It suggested a number of strategies that could help, including fiscal localism, local food production and the creation of local complementary currencies as steps to sustainable low-carbon economies.

Three alternative models

The triple bottom line (TBL) is an accounting framework with three criteria: social, environmental (or ecological) and financial. In traditional business accounting the "bottom line" refers to the profit or loss (which is usually recorded at the very bottom line on a statement of revenue and expenses). The triple bottom line adds two more "bottom lines": social and environmental (ecological) concerns. With the ratification of the United Nations and International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI) TBL standard for urban and community accounting in early 2007, this became the dominant approach to public sector full cost accounting. When a company works from this principle, it strives to promote the natural order as much as possible, or at least not to cause any damage and to minimize the impact on the environment. Social justice and equitability refers to fair and beneficial business practices with regard to employees and the community and region in which a company does business. A company devises a reciprocal social structure in which the well-being of corporate, employee, and other stakeholder interests are interdependent.

A theoretical model that offers an alternative vision is doughnut economics. The model is to help us visualize how we can realize the needs of everyone within the carrying capacity of the Earth. Not unlike Roadmap, the basic diagram is a circle, with a hole in the center (hence the name). The gap in the center shows how many people do not have access to basic necessities such as health care, education and housing. Space out beyond the crust indicates the extent to which the ecological ceilings (planetary boundaries) on which life depends are exceeded. The diagram was developed by Oxford economist Kate Raworth in a report for Oxfam called A Safe and Just Space for Humanity. She developed the model further in her book Donut Economy: Seven Steps to an Economy for the 21st Century (2017). A superb set of animations describing her work will be found here.

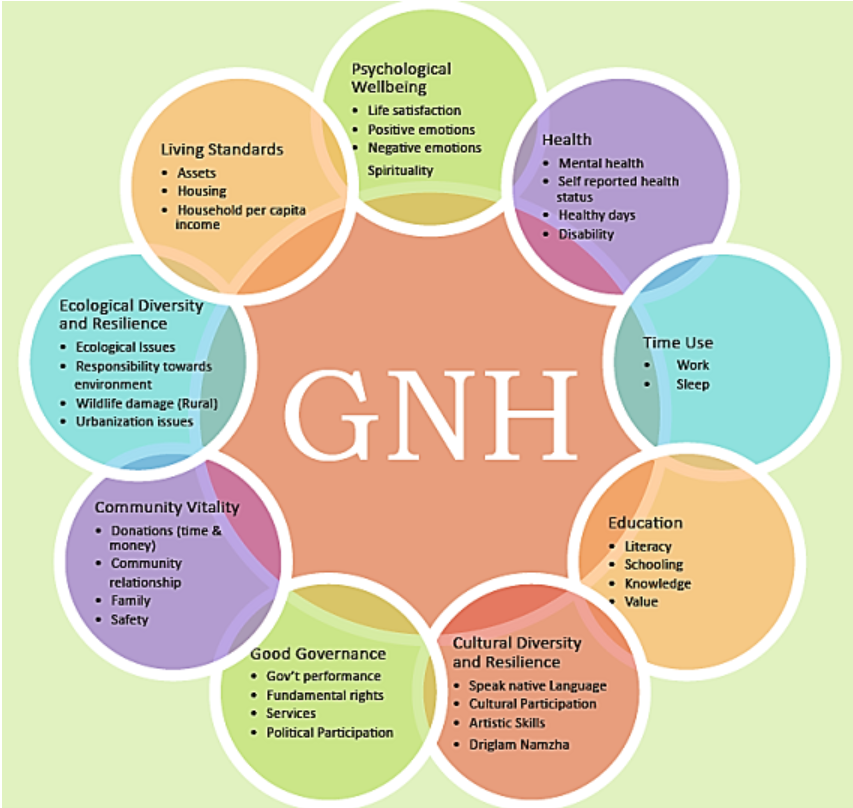

Thirdly, we want to bring the “Gross National Happiness” model to your attention. It is the counterpart of Gross National Income. This is the goal of the government of Bhutan, (which incorporated the concept into the constitution in 2008) to prioritize and measure quality of life by a number of indicators. After several international conferences, Buhtan submitted a resolution on happiness to the UN. Resolution 65/309 “Happiness: towards a holistic approach to development” was adopted in July 2011. It urged member states to follow Bhutan's example and measure happiness and well-being.

GNH's nine domains are psychological well-being, health, time use, education, cultural diversity and resilience, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity and resilience, and standard of living. Each domain is composed of subjective (survey-based) and objective indicators. The domains weigh equally, but the indicators within each domain differ in weight. According to the World Happiness Report 2019, Bhutan is ranked 95th out of 156 countries. In the top five were: Finland, Denmark, Switzerland, Iceland and Norway.

Despite some criticism, the concept of Gross National Happiness broadens the vision of well-being and puts it at the center. This is a valuable contribution at a time when economic equality, prosperity for all, and especially the real “bottom line” of psychological well-being are too often ignored.

Much thought and work is going on in the whole area of economics. One example is the New Economy Coalition

Obstructive nonviolence & economy

Up to now we have been illustrating the rich world of economic Constructive Program; but inequality is very often, along with political domination, a frequent cause for which people rise nonviolently. Our own Occupy Movement, which was not well planned (no alternative methods) or very effective beyond raising awareness to some degree about the enormous wealth disparity created by modern culture, was an example. As sociologist Ted Gurr showed in Why Men Rebel, there is a clear line between “poverty,” which is uncomfortable, and “destitution,” which is unendurable. When it is crossed, rebellion often ensues, and they are sometimes (though not often, unfortunately, nonviolent, or at least non-violent (meaning they stop short of physical coercion but may not be aimed at converting the mind and heart of the opponent). Classic example are tax refusal and the boycott, which has worked in South Africa against apartheid, the U.S. Civil Rights movement -- also against a kind of apartheid -- and many other places, including the highly effective boycott of British cloth goods in the Indian freedom struggle. Property destruction can also be considered nonviolent -- provided it’s your own property!

Reflection & discussion

How can you contribute to a needs-based economy in theory and/or practice? What method “speaks” to you?

Identify the principles of nonviolence/nonviolent organizing that you see in the examples of this section.

Add one or two examples of constructive or obstructive nonviolent action and share with the group. They can be examples that haven't happened yet. In fact, many of them have not!

Consider how your example could be carried out successfully and eliminate or substantially reduce the need for resistance/obstructive actions in the given area.